by Grigorii Sedelnikov

Six months ago, I had a cultural shock. My entire career as a QA Automation Engineer was spent in outsourcing: stable, predictable, even comfortable at times. But during the January holidays, I had a thought for the first time in ages: I’m almost 30, a confident senior, and yet it feels like I’m standing still.

All I did was toggle “open to work” on LinkedIn, and unexpectedly got an offer from a product company. I went to the interview “just to take a look” and stayed.

This article is an honest take on how work, the approach to quality, and life in general change when you switch from outsourcing to product. No sugar-coating, just facts. I’ll share what surprised me, what delighted me, and why releases no longer give me tachycardia. Maybe my experience will help someone decide to leap.

Onboarding and Paperwork

Theatre starts with the cloakroom, and a new job starts with onboarding. And here, onboarding turned out surprisingly pleasant.

There were just two interviews. The first was with HR: they introduced me to the company and team, and asked about salary expectations. The second was with the backend QA manager — shoutout to Vova! Funny enough, I had read his Habr article long before he interviewed me.

All paperwork happens through a personal account. No papers, no running around with your passport. Contract, payment details, and everything else are uploaded in a couple of clicks, and you’re already in your probation period. Expense claims for conferences, software, and education are also handled online.

And if something goes wrong? You can message the CEO directly in Slack. Seriously. Later in this article, I’ll talk a bit more about bureaucracy, but the kind that doesn’t make you grind your teeth. Almost.

Documentation ≠ Bureaucracy

At my previous job, I churned out “explanatory notes,” “user manuals,” and other documents the client would skim once, nod, and then forget forever.

Here, it’s different: there’s a dedicated technical writer, and their work doesn’t go into a drawer. Everything lands in a living, structured Confluence with headings, a table of contents, proper search, and no archival dust.

The writer isn’t locked away in an ivory tower. They work closely with developers and QA: short sync calls help clarify details without breaking flow. As a result, documentation is not “for the sake of process,” but genuinely useful.

Even AI now helps describe code and tests. Most of the time, you just tweak the wording. And honestly, documentation is like revising past lessons: great for memory, super handy for the team.

And yes, there’s nothing sweeter than finding your own article in Confluence and finally understanding what the heck you wrote a year ago.

Learning and Internal Knowledge Base

I already mentioned that the company reimburses external courses. But the real gem is the internal learning available to everyone right away.

We have a library of internal meetups: a media archive of talks about technologies and processes actually used in the product. Everything is curated and to the point. No need to waste evenings hunting for courses or sifting through dubious speaker reviews.

Bonus: If a technology is already in use, there’s a good chance you’ll face it soon. Knowledge goes straight into practice.

Special mention: the QA culture here is mature. The team includes SDETs who don’t just build frameworks, but make them pleasant to use, stable, and free of debug voodoo. Working with them helps you grow as a coder, write stable code without crutches and print()s in production.

“Push it to the repo and hope for the best”? Doesn’t fly. Every piece of code goes through an SDET review — tough but fair, and that’s where growth begins.

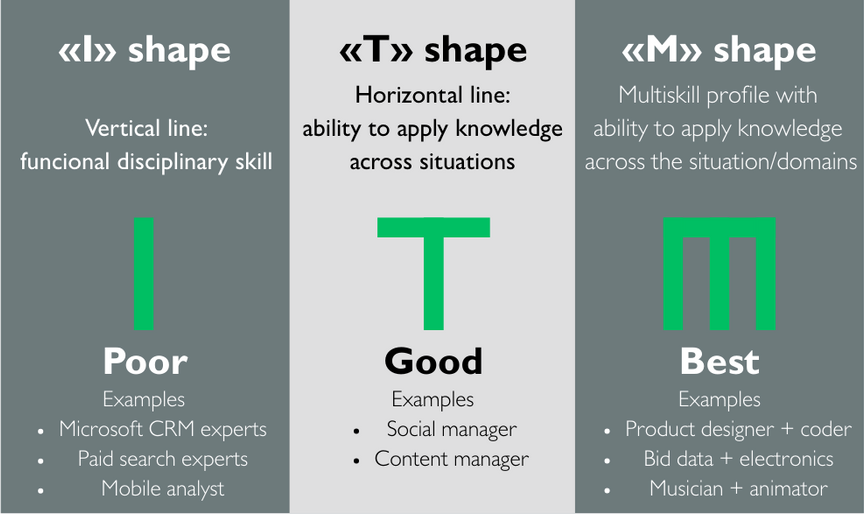

(On page 3 of the original file, there’s also a useful visual comparing I-, T-, and M-shaped skill profiles, showing the value of broad, cross-functional knowledge.)

How We Handle Releases

The next shocker: releases. But don’t cringe; here they’re not about late-night panic deploys or Tuesday burnout.

The process is set up properly. You’re on duty, but you’re not walking through a minefield. Everything is planned, no panic.

Each release has three simple steps, about 30 minutes each:

- Run automated tests,

- Analyse results and write demo notes,

- Prepare a release map — instructions for whoever deploys.

For a two-week sprint, that’s at most an hour and a half. That’s it. No nerves, no insomnia.

Releases are phased: first staging, then demo or prod. If something breaks on staging, devs jump in immediately. Nobody points fingers at QA. And such cases are rare; most bugs are caught earlier in test environments. Those environments mirror production closely and are monitored automatically.

Best part? No manual regression. No clicking through checklists for two days straight. Auto-tests run, release goes out, nerves intact. Life is good.

Real Communication

Enough about tech, let’s talk people. The most surprising part here? Communication actually works.

Message any manager, any level, you’ll get an answer. Sometimes in hours, sometimes in minutes. Even if you’re a newbie and nobody knows you yet. That’s especially critical in those first weeks when you feel like an intern lost in a foreign office.

If things don’t click with your current manager, you can escalate higher. Nobody pretends you don’t exist. All managers are in Slack. Don’t know who to ping? Open the internal org chart and find the right person. Transparency at its best.

Another plus: open calendars. Forget an invite, or just want to listen in? Jump in. Nobody will slam the door in your face.

Downside? Lots of meetings. But that’s the price of a distributed structure and dozens of independent teams. Like spaceflight: without docking, everything falls apart.

There are also regular 1:1s with your team lead, which you can set to your needs: weekly, monthly, whatever. Discuss tasks, vent about comms, or just breathe. A lifesaver during onboarding, like a glass of water after three days in the desert.

I got lucky: I joined during a transformation period and had two leads at once. Learned a lot and even made myself a secret cheat sheet (not sharing it!).

Impact on the Product

What’s the most important thing for a tester who’s seen some things? For me, being able to genuinely influence the product and processes. Not just close tasks, but see your ideas make a difference.

When you join a new team, you bring a fresh perspective. Sometimes you spot issues others have grown blind to. And here, that initiative isn’t ignored, it’s encouraged.

Real example: I’ve been with the company for about six months and already suggested an improvement that solved a business need. One of our core projects, the platform’s big calculator, is a separate service. Testing its functions isn’t always easy to combine with testing other services. For example, checking client risk calculation required integrating core testing with order placement (handled by another service). It was hard, but worth it!

The company also has performance bonuses, and they’re not just about numbers. Want to improve a process? Suggest it. Found a weak spot? Speak up. Got an idea? Share it. Here, it’s seen as a contribution, not criticism. If implementation needs extra work, you’ll get help. Discussions are open, managers are approachable, and bureaucracy doesn’t get in the way. That’s one of the biggest perks: you’re not a cog, you’re a participant.

Deadlines and Quality

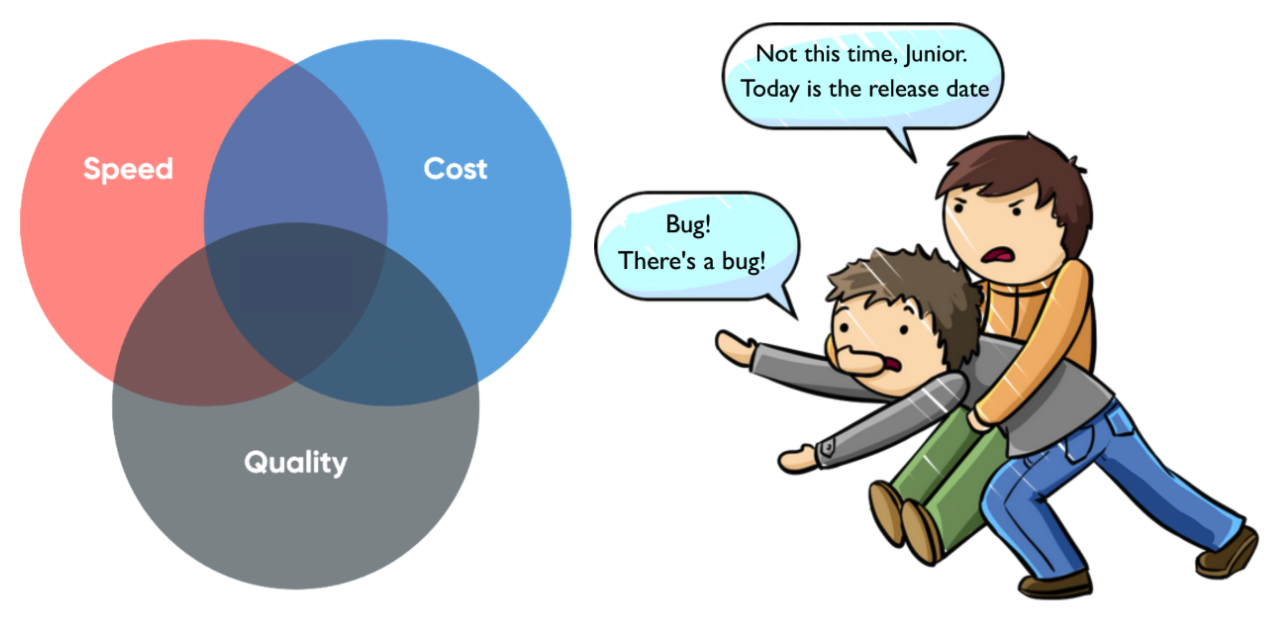

If you’ve read this far, congrats. Now comes the part that makes some people twitch: deadlines and quality. The bane and life of every QA.

How do you balance between two extremes? A prod bug is costly. Reputation first and foremost. So the priority is always the same: quality.

Didn’t have time to properly test a feature? It doesn’t go to release. Yes, it might get postponed. And that’s fine. No “let’s ship it to staging, maybe it won’t blow up.”

Everything hinges on planning. Risks are assessed upfront, and buffers are built in. On schedule? Pull something from the backlog. Behind? Do what’s planned, but do it right.

Force majeure happens, but releases generally stick to a schedule. I remember my first: feature barely tested, release tomorrow, I panic. Old instincts: test till night, fueled by nerves and coffee. Then I realised: here it’s different. Better to postpone than ship a bug. Attention under stress is like a raccoon under headlights; the bug slips by, then incident and postmortems.

Release only happens after QA approval. Not a recommendation, a rule.

How we plan sprints:

- Only count net time, excluding duty shifts, vacations, and holidays.

- Estimates are given by the person doing the task, who’s already in the know.

Two simple points, but they beat any process. No fakery, no “maybe we’ll hack it in a couple of days.”

Conclusion

The article title wasn’t just clickbait. For some, this story might sound like paradise; for others, boring without release-deadline adrenaline. Everyone decides for themselves.

As for me, I was amazed at how different things could be.

At my previous job, I hopped from project to project, switched domains, and lived in an endless launch cycle. Here, there’s no such “variety” — but I don’t want it. Now I want to go deep into one product, refine what I’m responsible for, and finally feel: I’m not just a cog, I’m part of something real.

What turned out to be important for me:

- Work without burnout, but with high quality.

- Influence the product, not just click test cases.

- Be heard and make real changes.

- Ship releases calmly — already five, not a single grey hair.

- Learn things you actually face in prod.

- No paper-chasing or stamp-collecting.

That’s my experience. Maybe it’ll resonate with you. Or maybe it’ll make you think. Either way, don’t be afraid to press the buttons you used to avoid.

Disclaimer: This article reflects the personal views and experiences of the author. It is shared for informational purposes only and does not necessarily represent the views of the company.

Este artículo se presenta a modo informativo únicamente y no debe ser considerado una oferta ni solicitud de oferta para comprar ni vender inversión alguna ni los servicios relaciones a los que se pueda haber hecho referencia aquí. Operar con instrumentos financieros implica un riesgo significativo de pérdida y puede no ser adecuado para todos los inversores. Los resultados pasados no garantizan rendimientos futuros.